A Frank Conversation About Democracy

Roberto Bechi | Tours by Roberto

The subject of democracy was a challenge for me because I wanted to delve into it as a principal, in human terms, avoiding what I consider to be less enlightening political debate. To do this, I decided to arrange a conversation with some foreign nationals living here in Italy, which we conducted—how else, these days—in a Zoom Meeting.

I invited Bridget and Arnault who come from Cameroon and Hossein from Iran, all of whom now live in Italy. Before recording our meeting I explained my own thoughts on Western democracy, which I will include here in my conclusion.

The historic Republic of Siena lasted for more than 400 years (1125-1555 AD). The construction of its Town Hall or Palazzo Pubblico began in 1297 and remains an iconic representation of democracy.

Image | Trish Feaster, The Travelphile

They, instead, are the stars of the video. To get the ball rolling, I asked my guests two questions: (1) What their first memory of any concept of democracy was, and (2) whether, arising in their own geographical homelands of Africa and the Middle East, they could imagine a democratic political system taking strong roots in their country? If so, I wanted to know if it would be original in shape, not simply imported from the West.

I was sure that these questions would provide food for thought, and indeed I learned a lot from them. For example, Bridget stressed how her country, even if it calls itself democratic, actually has only one political party. In any case, she notes, their concept of democracy is the Western one, adopted more or less in the same way as so many aspects of colonial Africa (borders, languages, and so on) were dictated by the European powers. A long-time resident of Italy, she hopes that one day many Africans will be able to return to their home countries, and when they do, take cues from the countries that hosted them. She envisions these peoples building a new society which reflects the many and varied viewpoints of its returning peoples. Bridget also lamented the ways in which Western mass media influence Western public opinion with images of a poor Africa and a rich west. To her mind, Western politicians are guilty of not telling the whole truth about the exploitation of African resources and people.

Arnault, also from Cameroon, has long had a passion for political science, and truly surprised me with news which,I confess, I had known nothing about: a civil war is currently underway in his country. It was a poignant reminder of how little attention we in Europe often pay to his area of the world, despite it having been the very cradle of humanity. Not only that, he reminded me that some of the democratic principles we live by were already present in ancient Egypt. He believes fervently that African schools should teach students the principles of a civilization that has given so much to not only African, but also world culture. He stressed that for him, a democracy is relevant only if the rules that the people have created are respected by them, it is not enough just to write them in a constitution. A constitution must be alive in the hearts of the citizens who live under it.

Hussein, who came to Italy as a student from Iran, echoed this point in stating the obvious—that Iran may be a republic in name, but in fact it is an iron-fisted theocracy. His most passionate remarks regarded the roles of free speech and a free press. He reminded us of how much the Iranian regime has absolute power and that it does not serve the interests of the people but only of their followers. Above all, it is able to do so because opposition voices are never heard. He seems to view the American model as a good example of democracy, but closed his remarks by reminding us that even if imperfect, there is no superior alternative to the Western democratic system.

I too believe that democracy is the foundation underlying every aspect of our lives, although too often we take it for granted. Before the recording, I shared my thoughts with them about it. I was born in Siena in Tuscany in Italy in 1964 - for me democracy was a fact. I never perceived it as something alien. I was taught that my grandparents had fought for it and that my people had always treasured it. I shared a text with them that can be seen as the background to our conversation on Zoom. It is the Senese constitution of 1310 which had been translated into vulgar Italian from Latin for the first time. What Arnault declared, the government of the Sienese Republic had already foreseen - that the constitution must be alive for its people. It was kept in a public room chained to a table and available for viewing. Because it was written in the language they spoke, the Sienese were able to understand what the laws were, as well as the rules that the government was obliged to follow to provide for the public good. (Even today, the use of “legalese” can get in the way of that understanding).

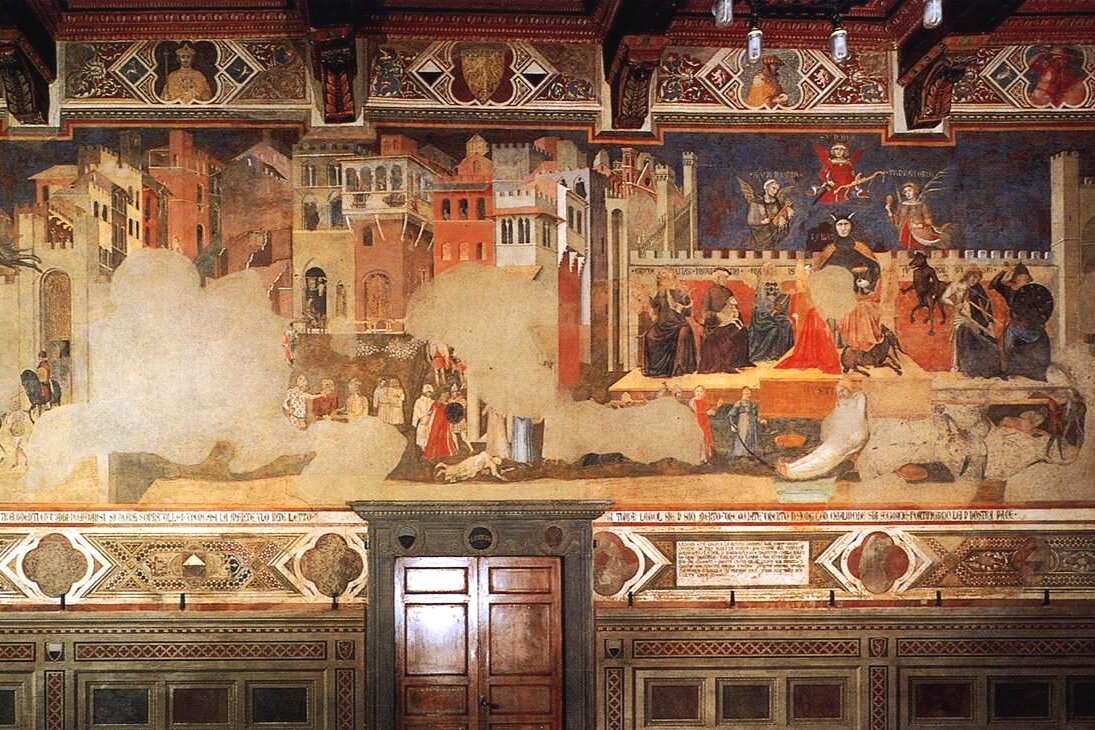

The Effects of Good and Bad Government, Allegory of Bad Government

Image | Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Web Gallery of Art, Wikimedia Commons

The Effects of Good and Bad Government, Allegory of Good Government

Image | Ambrogio Lorenzetti, José Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro, Wikimedia Commons

The Effects of Good and Bad Government, Allegory of Good Government

Image | Ambrogio Lorenzetti, Google Cultural Institute, Wikimedia Commons

I also showed them a complex allegory fresco by Ambrogio Lorenzetti 1339 entitled “The effects of good and bad government”. Commissioned by the government, the fresco illustrates theological and secular virtues as the supreme guide of city government. Without social justice, there is no collective prosperity; to the contrary, under a tyrant, there being no virtue and justice, the city is doomed to fall into oblivion. For me, this text and the Aristotelian message of the frescoes are still one of the most concrete expressions of the dawn of democracy as we know it today.

I hope you enjoy listening to our conversation as much as I enjoyed being a part of it. You can watch it for yourself right here. I look forward to reading your own comments and thoughts on democracy!

A frank conversation about democracy with African and Iranian ex-pats living in Italy, moderated by Italian guide Roberto Bechi from Siena.