An American Expat’s Take on Early Childhood Care and Education in Italy

Lisa Anderson | Lisa’s Dolce Italia

Regardless of whether you have children between 6 months and 5 years old, you probably know someone who does. And if you have ever talked to them about childcare, you certainly know what an ordeal it can be to find high quality childcare. Let’s not even talk about affordability because in the United States, affordable daycare is pretty much non-existent. The Public Broadcasting System (PBS) ran an interesting series during their news hour the week of July 12, 2021 called “Raising the Future: America’s Child Care Dilemma.” It got me thinking just how lucky we are in Italy because early childhood education is one of the best aspects of the Italian education system.

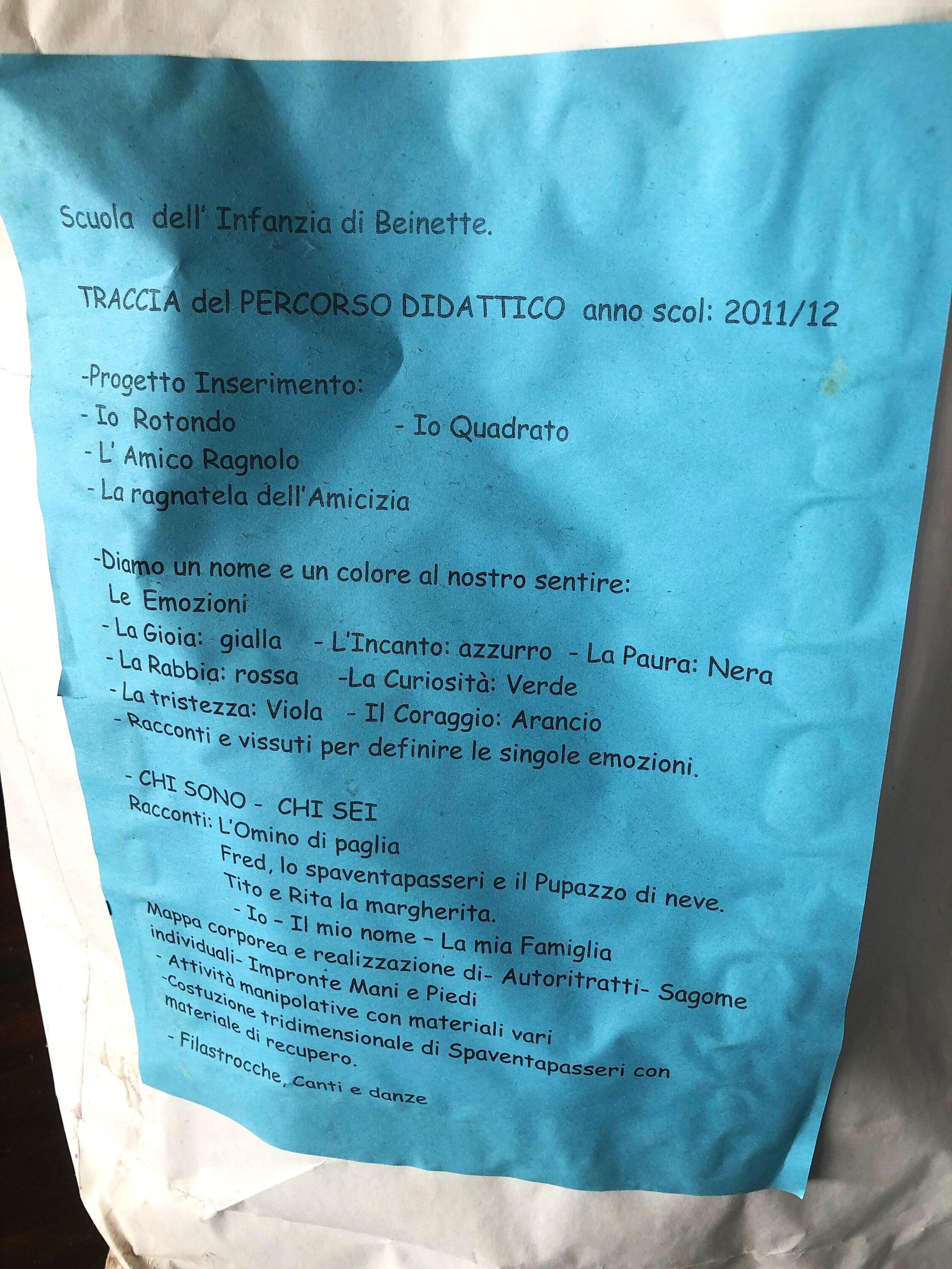

Image | Lisa Anderson

There is a ton of research proving that early childhood education gives children a head start in life. It establishes a routine, teaches children invaluable language skills (even without putting any emphasis on learning how to read and write), and teaches them critical social and emotional skills. Affordable early childcare also frees up time for parents to work and apply that extra money to other necessities, which creates stability and allows for more quality time with their kids when they are at home. In countries in which there are also a lot of immigrant families, it helps families integrate more easily, particularly in homes where the first language differs from the local language. By the time a child who started daycare at the age of three begins elementary school, they will have the basic language skills needed to thrive and can even help their parents learn.

When my children were attending daycare and elementary school in Italy between 2004 and 2012, our only out-of-pocket expense was lunch, €3.60 per day at the time (since we live within walking distance of the school), and a couple of new grembulini, (smocks) that our kids wear to school over their clothes.

One minor out-of-pocket expense for daycare and elementary school: grembulini or smocks.

At the same time, my friends in America were paying $1200-$1500 per month per child for daycare in the Seattle area. In the United States, it is not uncommon for people to spend 20 to 30 percent of their monthly income for childcare—an enormous burden for lower- and middle-class families.

Italy is by no means the best country in which to raise children. The 2021 US News & World Report “Best Country for Raising Kids” report ranks Italy in 16th place in the 2021 , whereas Canada is ranked 5th. Despite their placement, Italy’s early education system, from my perspective, is excellent. There is early daycare available, (Asilo Nido for children between the ages of six months and three years), and regular daycare (Scuola Materna), either part-time or full-time, available for children between three and six years of age.

There are not enough Asilo Nidos to accommodate the demand; only 24% of the population benefits from the state managed centers, with preference given to families in lower income brackets. In a country where the cultural norm is to stay close to home, it is a general assumption by Italians that grandparents will babysit, and most of them love it. It creates a bond that lasts a lifetime and helps instill the cultural value of family that Italians hold near and dear. For families that don’t have the luxury of built-in babysitting, there is a great need to improve on the lack of public Nidos. Both communal (city-run) and private daycares, called “baby parking,” fill this gap. Costing between €300-€550/month, this is expensive by Italian standards, where the average gross salary ranges between €24,000-31,000 depending on the region.

Where the Italian school system steps up beautifully is for families with children between 3-6 years old. Scuola materna is not mandatory; children are not required to start school until 1st grade, but I have never met a parent who hasn’t used it at least part time. Italians believe that socializing their children is incredibly important, and that children should be with other children. In families where having only one child is now the norm, daycare is essential for meeting this need.

Each class at scuola materna consists of a two-teacher team with a maximum of 26 children—although 20 is considered ideal—and the schools do their best to create sections that reflect this. They also try to create stability by keeping kids with the same teachers each year.

School days consist of free play, organized playtime, storytelling, music, movement, and lots of art. Still, it’s not a perfect world, and some cuts have been made over the years. At the beginning of the school year, parents are given a list of supplies that get “donated” to the school: a ream of paper, colored pens, a bag of cornmeal (for the “sand” table), watercolors, and paper towels. Each child is also expected to bring their own cot and blanket for naptime, a toothbrush for after-lunch brushing, an extra smock that is used for art projects, and a pair of slippers that are worn in the classroom. Shoes are put back on for recess outside! Each school has its own needs so the list might vary a bit, but it’s never a huge expense, and aid is available.

A scuola materna in Cuneo, Piemonte in Italy.

Image | Lisa Anderson

Italian daycare gives parents three options for time spent at school, all of which start in the morning with drop off between 8:30-9:00am. Kids can then be picked up before lunch at 11:30am, after lunch at 1:30pm, or after naptime at 4:30pm. Third year students no longer nap but have quiet playtime while the younger kids are sleeping. Most children stay at school for lunch and learning how to sit and eat properly with utensils and help clean up is part of their education.

There are two expenses that families pay for outside of meals only if they need extra services. Most of these costs are set by individual towns but are very similar across the country. Where I live in the province of Cuneo, if you need to drop your kids at school early, 7:30am, it costs €55 per year. School bus service is also privately paid and ranges between €300-500 per year, depending on whether you live inside or outside the city limits and how many children in your family are attending school.

Italy’s educational spending is low in comparison to other European countries, but even so, I will argue that its early education system is still better or at least more consistent than what we have access to in the US. It is especially helpful to low-income families and important to keep the income gap from widening. Decades of research have proven that early childhood education has an enormous impact on long-term, life-affecting outcomes; children who enter intensive preschool programs are more likely to graduate and pursue higher education, less likely to struggle with substance abuse as adults, and less likely to be arrested. Since the children really are our future, this is an issue we need to focus on and learn from countries that do it well.

For further reading on how early childhood education makes a difference, these articles are worth reading.

• Early childhood education yields few academic benefits — but still has lifelong effects