Is Rebirth Utopian?

Siena’s City Hall, Palazzo Pubblico

Image | Anderzej Otrebski, Wikimedia Commons

In his telling of the story of King Midas and the demon Silenus, supposedly the wisest creature on Earth, Nietzsche notes that upon finally hunting the demon down, King Midas demands that he answer the question “What is the best and most desirable thing for man?” Silent at first, Silenus ultimately bursts out with a contemptuous laugh saying, “Oh, wretched ephemeral race…why do you compel me to tell you what it would be most expedient for you not to hear? What is best of all is utterly beyond your reach: not to be born, not to be, to be nothing. But the second best for you is—to die soon.”

Nothing could express a purer pessimism, the desire to never have been born and to be nothing, therefore to refuse one's existence! That is the essence of tragedy.

Birth, then, is the utter opposite of tragedy. While it is true that we are born with physical pain and causing that pain, almost immediately, we encounter the purest love—that of our mother. That is when we begin to understand the meaning of hope. If having hope were the definition of being born, then one would want to be reborn every day. I like to think that perhaps being reborn is the training ground for our existence.

Physical rebirth is impossible, of course. That doesn’t mean that the word has no meaning. We talk about being reborn both in religious or other contexts because it gives us that hope: hope for the future. We often use this term to indicate important moments in our life. How many times have we said, "I feel reborn" after a difficult moment has passed?

Being a guide, I am also curious about the idea of rebirth in history. Almost everyone in the Western World studies the Italian cultural and artistic Renaissance, which of course has at its root the word for rebirth. Historians, though, do not tend to love the term, because although there is a clear cultural movement during that period, no cultural idea “dies”—nothing is reborn. To consider that the Renaissance meant a better or more enlightened life is even ironic; there are history books, for example, which date the beginning of the Renaissance precisely to 1492 with the discovery of the New World. Significant though that event was, the very same Queen Isabella who had funded the journey of Columbus was busy expelling from Spain all of the Muslims and Jews who refused to convert to Catholicism. Meanwhile, Florence, the heart of the Italian Renaissance, was controlled by the Medici, who essentially ruled as dictators; and the Inquisition brutally eradicated heretics. There are any number of events during this same period which could hardly be seen as a “rebirth of civilization”.

Moreover, even the Middle or “Dark” Ages replaced by the Renaissance were a nineteenth-century invention. There is no specific date of a beginning or end of a cultural movement because each has roots in the previous one and innumerable causes and effects. Society, art, and people themselves—we are all changeable.

Consider another historical episode that I find profoundly moving. At the height of the Middle Ages, in 1337 the Franciscan Capuchin monks commissioned a Sienese sculptor/architect, Lando di Pietro, to create a large wooden crucifix to be hung in front of the altar of the Basilica dell'Osservanza, located a few kilometers from Siena.

Basilica Dell’Osservanza

Image | Liga Due, Wikimedia Commons

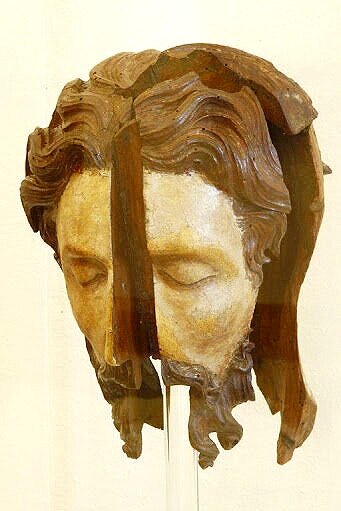

Centuries later, during the Second World War, bombing of the Siena railway station by the Allies, in an attempt to slow down the retreat of the German forces, missed their target, unfortunately destroying the central body of the church. When the rescuers went to recover the bodies of some monks and collect the objects not yet destroyed by the flames, they realized that the only piece of the ancient crucifix that remained intact was the head of Jesus. As soon as they picked it up, the head split into two equal halves. Indeed, Lando had not carved it from a single piece of wood but had instead glued two pieces together, leaving a small space where he placed a scroll with a prayer in Latin:

“Tucti e santi et sante pregate Yhu Xpo (Gesù Cristo) figluolo di Dio che abbia misericordia del detto Lando, et di tutta sua famiglia, che li faccia salvi et guardili da le mani del nimicho di Dio. Yesus, Yesus, Yesus Xpo filius Dei vivi, abbi misericor di tucta el omana generazione.”

May all the Saints pray to Jesus Christ, son of God, to have mercy on Lando and his family and save them from the hands of the enemy of God. Jesus, Jesus, Jesus Christ, Son of the living God, have mercy on all human beings.

Crucifixion head of Jesus by Lando di Pietro

Image | La Via della Santa

The artist's faith is striking, but even more so is the last sentence of this utterly secret, private prayer, "have mercy on all human beings".

Ambrogio Lorenzetti in his frescoes of the "Good Government" in the Palazzo Pubblico of Siena, also demonstrated a concern for humanity far beyond his own tiny circle. Albeit in a much more secular way, he wanted to protect posterity, warning man that there is no peace unless there is social justice. Certainly these artists lived in a period that some history books describe as dark, but this selfless sentiment makes us reflect on why they rightly considered themselves modern.

If the “Renaissance” is no more “reborn” than the “Dark Ages”, which were not really dark, is the idea of rebirth meaningless in history? I really believe that it is a prerogative of human beings to be able to catalog the past as best as they can, and project their existence into the near future. Rebirth is a concept that helps us to hope for a better future or if there is no future, a better afterlife. Having that hope—the hope that we can begin again, be born again—distinguishes us from other living beings. It soothes the physical and psychological pains we feel, making us believe that we will be well again, be loved again, be better people tomorrow than we are today.