The Journey of the River Forth from Source to Mouth

Course of the River Forth

Image | Juxx, Wikimedia Commons

My journey begins on the steep slopes of Ben Lomond in the Loch Lomond and Trossachs National Park. There was quite a celebration when this first National Park was established by the Scottish Parliament in 2002, although some time had passed since John Muir from Dunbar in East Lothian was instrumental in establishing Yosemite National Park in Central California in 1890.

At the beginning of my journey my name is Abhain Dubh meaning “black river” in Scottish Gaelic. I tumble down the mountain to Duchray Water and then into Loch Chon, much appreciated for its sheltered water after my hurtle down the hillside. I can relax in this magical place and enjoy the playfulness of the resident kelpie (a shape-shifting spirit that inhabits lochs in Scottish folklore) and one of the world’s largest populations of fairies—but not for too long, as I must be on my way into Loch Ard.

Loch Ard

Image | Mike Shuttleworth, Pixabay

As I travel through the loch, I’m distracted by the very distinctive smell of whisky distilling. Just a few yards away, hidden in the forest, is the ruin of Wee Bruach Caoruinn where illicit whisky distilling took place in the 18th century. It’s hard to believe today, but in 1788 the Excise Act banned the use of stills making less than 100 gallons at a time, so illicit stills cropped up all over the hills and glens (deep valleys in the Highlands). I can still hear the signal from the lookout, raising the alarm that excise men were on their way so hide all the equipment in the surrounding forests.

As I come to the aptly named Lochend Cottage, I squeeze under the wooden bridge in the residents’ back garden and through their boathouse. My name changes to River Forth at this point and I take on a different energy as I flow purposefully towards Aberfoyle.

I can remember back to when Aberfoyle was a small settlement on the site of an ancient fortress built by Aiden, Prince of the Forth, in the 6th century. Nowadays, it’s a bustling tourist centre, thanks largely to the literary works of Sir Walter Scott. An old oak tree grows along my banks and if you look up you'll see the poker made famous by an incident in Rob Roy (a novel by Sir Walter Scott, a Scottish historical novelist, poet, playwright and historian at the turn of the 19th century) when Bailie Nicol Jarvie makes use of a poker to fight with the Highlanders in Aberfoyle. The real Rob Roy was a weel kent (well known/ well recognised) figure in Aberfoyle, and I’m reminded of his cattle rustling and his “blackmail” business carried on close to my banks.

Before I leave Aberfoyle I always glance up to Doon Hill, or Fairy Knowe as it’s called today, and to the Fairy pine at the top. The Reverend Robert Kirk, the local minister in the late 1600s, believed that this hill was the gateway to the world of fairies which he described as the “secret commonwealth.” A scholarly man—the first person to translate the bible into Gaelic—he would often walk by my side, deep in thought. Like most people in the 17th century, he believed in witchcraft, spirits and pagan rituals and became so obsessed by the study of fairies that he even described their appearance, ways, habits and secrets in a book. Local folk believed that by revealing their closely guarded secrets, he so enraged the spirit people that they killed him on Doon Hill, where his body was found on 14 May 1692. To this day it’s still believed that Reverend Kirk’s soul is inside the lone Scots Pine tree on top of Doon Hill.

Just after Aberfoyle, I well remember travellers talking about the wee lassie who, in 1547, was staying just a stone’s throw to the north, at Inchmahome Priory on the Lake of Menteith. She was Scotland’s Queen—Mary, Queen of Scots—taking refuge from the ire of Henry VIII of England, who wanted to exert power over Scotland by marrying her off to his son Edward. I heard that she escaped to France and wouldn’t return until the summer of 1561.

I leave the beautiful hills and lochs of the Trossachs—sometimes known as the Highlands in miniature— and move slowly onto the flat carse lands (low-lying rich areas along a river) which today form fertile agricultural lands. As I meander my way across the carse, I reflect that it wasn't always like this. Over 8,000 years ago, a wet marshy plain that became known as Flanders Moss formed across the carse. Then I measured miles in width as I ran between the volcanic intrusions of the Campsie Fells and the Gargunnock Hills on my journey from the west. Today, the eastern part of Flanders Moss remains predominantly in its near-natural state and is recognised as the largest raised bog in Europe. As well as being an important habitat for wildlife, Flanders Moss also plays a key role for carbon sequestration acting as a carbon sink.

Flanders Moss

Image | Richard Webb, Wikimedia Commons

In recent times my width has been greatly reduced and this is due to the agricultural improvements that took place across Scotland in the 1700s. Lord Kames, the local landowner, encouraged the draining of his land and a three-mile-long channel measuring 3 feet in depth was dug from Blairdrummond Estate to meet up with my river course. This was both scary and exciting and would bring about a huge step change in my usefulness. A waterwheel was installed, and the top layers of peat were dug out and washed into my course to be carried down to my mouth and out to sea. Imagine the environmental impact!

People displaced by the Highland Clearances were encouraged to move here to dig the channels and drain the land. In return they could build their own homes and live rent-free for seven years. They were known as the Moss Lairds as they prospered on the rich agricultural land they were responsible for creating. The work was complete by 1840 and my course was set.

It’s at this point that I begin to change. I started life as a freshwater burn flowing from the high hills of Ben Lomond, gathering strength as I journeyed through the Trossachs and across the Carse, but now I am meeting the saltwater tide as it pulses in from the North Sea. I find this a difficult meeting of the waters, reflected by the turbulence that is visible here at Cruive Dykes.

It’s on this four-mile stretch that I meet many fly fishermen during the salmon and trout season who tell me that the Rocks pool is the most productive site, the fish enjoying the calm shelter of my banks. Most of the fishermen are local and the skills and knowledge of my pools, currents and tidal flow have been passed down through generations, creating a special relationship between me, as the river, and those who take the fish from my waters.

As I approach Stirling, the land through which I flow is so flat that I lose almost all my momentum. I begin to meander, twisting in one direction and then another, at times I seem to meet myself as I wind backwards and forwards in what is known far and wide as “The Links of the Forth.” My course takes twelve miles to travel only six miles as the crow flies!

The Links of the Forth

Image | Wikimedia Commons

I’m overlooked in dramatic fashion by the high rocky crags on which Stirling Castle and the monument to William Wallace are located. I am reminded that in the 1200s, the only crossing place from the north of Scotland to the south or vice versa was at Stirling, giving it great strategic importance. Not only did the settlement have the crossing point but it also had a large volcanic rock plug standing in the middle of acres of very flat marshy bog. In the very early days, they forded me here at Stirling before a wooden bridge was built. During the Scottish Wars of Independence, William Wallace defeated the English troops at the Battle of Stirling Bridge in 1297, and I like to think that I played an important part in his victory as many of the English archers and cavalry came to grief in my waters.

The wooden bridge has long since gone but even the four-arched stone bridge dating from the 1400s carries its battle scars. In 1745 one of its spans was blown up to prevent the Jacobites (supporters of the deposed king, James VII) entering the town of Stirling. It then had to be hurriedly rebuilt in 1746 to allow the Duke of Cumberland and the Government forces to pursue the Jacobites north. Alongside this old bridge is the newer Stirling Bridge designed by Scottish engineer, Robert Stevenson, and opened in 1832 and still very much in use today.

Just as it seems I’m intent on entering Stirling, I meander in another direction towards Cambuskenneth, a quiet little backwater that takes its name from Kenneth MacAlpine, first King of Scotland. It was King David I who founded an abbey, here on my shores, for the monks of the Augustinian order, but only the Campanile remains today. In the grounds of the abbey lies the grave of King James III and his Queen, Margaret of Denmark. Their grave was ignored for centuries and I remember the excitement when Queen Victoria, learning that one of her ancestors was lying in such a pitiful grave and location, ordered the restoration of the bell tower and graveyard.

I now decide to turn back on myself and flow westwards into the heart of Stirling. From the 11th to the early 19th centuries, Stirling harbour was a busy port with a bustling trade between Scotland and the continent - small sailing ships brought exotic foods, wines and spices from Europe and beyond. Links with towns of the Hanseatic League were strong, and Stirling had a particularly close relationship with Bruges in Belgium and Veere in the Netherlands. It was an exciting time for me as I listened to the different languages being spoken on the various ships from Europe. I can still see John Cowan, Auld Staney Breeks,(1570-1633 Stirling merchant and benefactor) standing at the harbour to check his ships and cargo.

In less troubled times, James IV built a Great Hall at Stirling Castle, designed to display his great wealth, intellect and standing on the European stage. He even had it painted in King’s Gold. Coloured with one of the most expensive dyes of the time, the castle stands out from the surrounding landscape and is visible for most of my journey. James IV hosted many banquets, entertaining the rich and famous of Europe, serving up amazing and unusual produce from home and abroad. I even heard of one feast where my link with the sea was honoured by the building of a miniature galleon in full sail, to carry the silver salvers laden with exotic food right into the banqueting hall.

Stirling Castle and the River Forth

Image | John McPake

Sadly, for me, much of the trade of goods shifted to Glasgow on the River Clyde after 1707, as trade with America became the new focus. It was fortunate that river travel became a much more attractive and comfortable alternative to the bumpy stagecoach for passengers travelling overland. In 1813 the first steamship service was introduced from Stirling to Granton for passengers wishing to visit Edinburgh, and soon three steamships were operating a daily service on this route. What fun, listening to the excitement of the passengers as they talked of their adventure to the big city.

During the First and Second World Wars, Stirling harbour thrived again as a gateway for supplies of tea to Scotland—an essential for any Scot! Trade slowly returned after the wars, but the few agricultural merchants based at Stirling found shipping here to be uncompetitive, due to high shore dues levied by the harbour's owners. Today Stirling's harbour is no longer in use, and I find it very quiet.

Stirling Rowing Club was established in 1853 and there was great activity until 1860 when it all went quiet for thirty years. I was delighted when the club started up again in 1891 and once again, not only rowing but also swimming became popular along my stretches at Queenshaugh. I loved the regattas which attracted boats and swimmers from all over Scotland. I remember the 1950s the swimming races, the greasy boom and the rowing races, pipe bands played, and bunting decorated the clubhouse. On my opposite bank, within one of my links, is Stirling Rugby Club. In the winter time I hear the spectators at the matches—loyal, noisy and enthusiastic fans, whether their team wins or loses.

As I flow onwards, I am joined by the Bannock Burn, which, it is said, flowed red with the blood of both English and Scottish soldiers on the day of the famous battle in 1314. Today a much healthier red is associated with my shores. Dr McIntosh lived at Lower Polmaise Estate and enjoyed the cultivation of apple trees within his walled garden. It is claimed that he took the seeds of his McIntosh Red Apple with him when he emigrated to Canada and these apples became one of Canada’s most famous exports.

I continue my meanders until I reach Alloa. Back in the middle of the 1800s, the port at Alloa was so busy with the import of wooden pit-props (support beams in a mineshaft) that a new larger dock basin was built. This was to support the mining industry that developed along my shores and even under my waters! Alloa remained a prosperous port until the opening of the Kincardine Bridge in 1936. The world’s largest swing bridge, it really improved road transport from Grangemouth further east along my shores. It was now cheaper and faster for ships to discharge at Grangemouth and for their cargoes to be brought by road to the factories at Alloa. I used to love it when the swing bridge opened to allow the shipping through. Nowadays I miss seeing the crew in the control tower high above the road deck since it was closed permanently, becoming a static bridge, in 1987. One consolation, of which I am immensely proud, is that it still holds the record for the world’s longest swing bridge. The 364ft central span has never been equalled.

Kincardine Bridge

Image | Paul McIlroy, Wikimedia Commons

In the 17th century, Culross, on my north bank, was a bustling little harbour exporting locally produced coal and salt and importing cargoes ranging from iron to the finest cloths, richest spices to the bright red pantiles which still can be seen on the roofs of the houses. The occasion that is foremost in my thoughts is when James VI visited the local entrepreneur, Sir George Bruce. Bruce was a brilliant engineer and had created a system to mine coal much further out from my shores. He built a moat pit which allowed a better flow of air into the mine and invited James VI to walk along the submarine tunnel to inspect this structure as the highlight of his visit. However, it will be a long time before I forget those royal screams of panic. He thought he was being murdered! He was not! But he didn’t risk returning by the tunnel, and instead a boat was sent out to fetch him.

Culross Palace, home of Sir George Bruce

Image | Palickap, Wikimedia Commons

Across on my south shores lies Grangemouth which, today, is Scotland’s oil refinery for North Sea oil. The oil itself is discharged from the tankers further east and piped from Hound Point to Grangemouth. I find it fascinating that I flow between Culross which is a beautiful little town caught in a time-warp of the 17th century and Grangemouth which is every inch a 21st-century industrial town.

James Watt came to work in secret on the improvements to the steam engine on my south shores at Kinneil. Imagine, it might have been water from me, the River Forth, that brought about Watt’s “eureka” moment that revolutionised the industrial world. Just a matter of a few miles away, Bo’ness pottery was busy producing wally dugs (thick coarse chinaware dogs) which became the “must have” in many homes up and down the country. I played my part in the pottery’s success as transport of this fragile cargo by water was essential to ensure minimum breakages.

Blackness Castle was built like a stone warship to fulfil a promise made by Archibald Douglas to James V that he would have a flagship strong enough that the “auld enemy” (England) could never sink it. This imposing structure sits on my south bank. Nowadays it’s a visitor attraction, wedding venue and film location, so I still witness activity around the Castle but much calmer than in the days of Mary Queen of Scots.

We are getting closer to where I enter the North Sea, but before I do, I have to flow past Rosyth Royal Naval Dockyard on the north shore. The Royal Navy came to Rosyth in the early 1900s, but before that, in 1860, the Channel Fleet anchored in my waters. What a sight, with thousands of spectators on either shore to catch a glimpse of the mighty “wooden walls.” A similar spectacle occurred in 1995 when the Tall Ships race entered my waters.

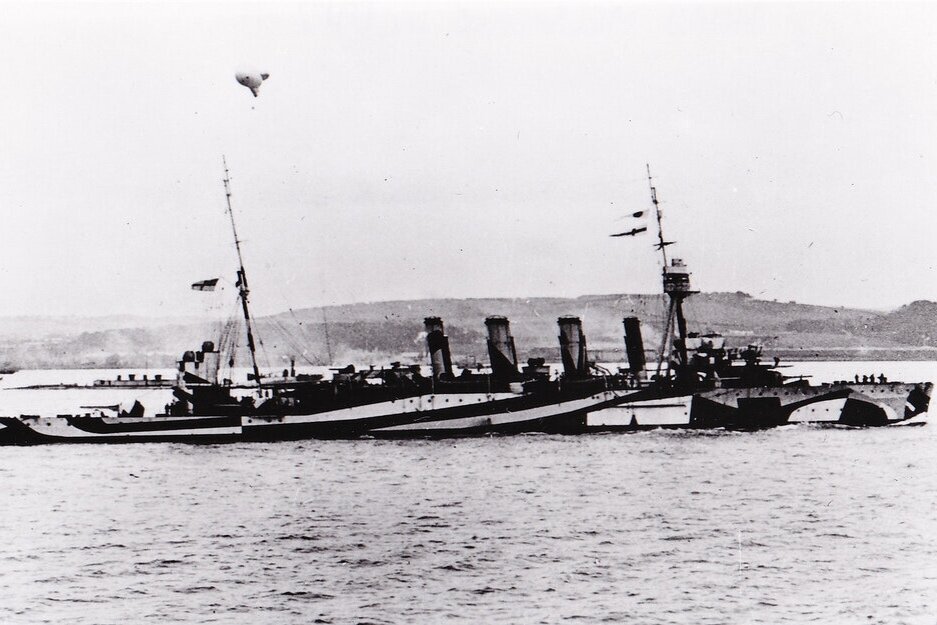

Perhaps the most spectacular sight came in 1918, when the entire British Grand Fleet, together with representative ships from the other allied powers— some 201 warships in total—assembled at the mouth of the Firth to meet the Imperial German High Seas Fleet (a further 70 ships) on their way to internment.

Rosyth, 1918 - the Principal Base of the Grand Fleet by John Lavery

Image | John Lavery, Imperial War Museum

HMAS Melbourne I in Rosyth 1918

Image | Public Domain, Wikimedia Commons

Today the cruise ships come in and, depending on their size, will either berth at Rosyth or drop anchor off Dalgety Bay and ferry the guests by tender to South Queensferry.

Back in the 11th century, Queen Margaret landed near Rosyth when fleeing from England at the time of the Norman Conquest. She married King Malcolm III of Scotland and established a ferry to cross over the Forth between the church at Dunfermline and the church at Holyrood. Later her son David I elevated those churches to Abbey status and the ferry was used by pilgrims. I find it hard to believe that this ferry ran continuously for 900 years. It was the building of the Forth Road Bridge in 1964 that put a stop to the ferry and I now have a further road bridge, the Queensferry Crossing, straddling my width. But it was in 1890 that the bridge that is most associated with the crossing from shore to shore was opened. What a day that was! The Prince of Wales drove in the final gold-plated rivet and the Marchioness of Tweeddale took the train's controls and drove the first locomotive over the bridge. This famous Forth Bridge is now a World Heritage Site.

Forth Bridge spanning the Firth of Forth

Image | Timo Newton-Syms, Wikimedia Commons

At this point I am changing from being the River Forth into the Firth of Forth. Perhaps I should explain the different sections of my length. Upstream from Stirling I am known as the River Forth; from Stirling to Queensferry, officially, I am the Forth Estuary and seawards from Queensferry bridges I am the Firth of Forth.

Just as my beginning is difficult to pinpoint, so is my ending. So many wee burns are tumbling down the north slopes of Ben Lomond. It is only after all that water has entered into Loch Chon that I feel my beginnings as I emerge into Loch Ard and I am officially named as the River Forth under the wooden bridge at Lochend Cottage.

My endings begin in the Forth Estuary, but I still feel like a river. It is after the bridges at Queensferry, when I find it difficult to keep in touch with both my north and south shores, that I am content that my work as a river is complete and happily hand the responsibility over to the Firth to take the waters through to the North Sea .